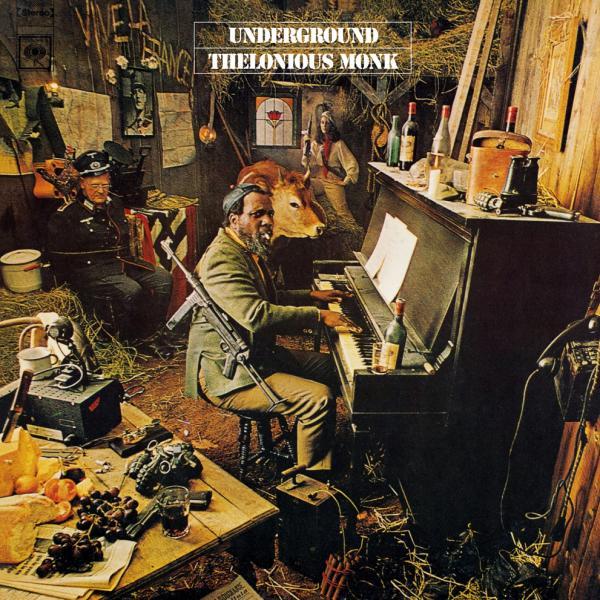

Thelonious Monk: Underground

Album #94 - June 1968

Episode date - December 28, 2016

Most of the jazz cats who defined a path for music in the ‘50s found themselves directionless in the crazy ‘60s. In that space of time, youth culture permeated society and had taken over, leaving little room for the sophisticated sounds of classic jazz.

With very few exceptions, the only jazz artists who thrived during those years were those who radically altered their styles to suit the changing times (Miles Davis is the obvious example here). Most jazz players took a curmudgeonly stance toward rock music, because they saw how it derailed their careers, pushing them into a corner while lesser musicians received all the attention. I don’t know what Thelonious Monk thought about popular music in the sixties, but I don’t think any of this bothered him or affected his music at all. He may be the only jazz musician from the previous era who moved smoothly into the sixties, remaining popular without making any distinct alterations to his sound.

In the ‘50s, Monk released some of the most important and exciting jazz albums ever recorded. His core genius rested in his ability to compose songs that were instantly identifiable as his, full of odd note choices and unpredictable melodic runs. His songs existed as firm proof that the ‘wrong’ note can sometimes be the most perfect note, and his unique sense of harmony extended to his solos as well. Over the course of three decades, he would often revisit his own compositions, releasing a variety of approaches to his material that never seemed to grow boring or redundant. How could anyone object when a master songwriter and true musical genius digs into his own songbook to provide fresh interpretations of compositions that had become true jazz standards, songs like “Well, You Needn’t,” “Round Midnight” Or “Straight, No Chaser”? On Monk’s previous album (titled “Straight, No Chaser”), released in 1967, he revisited three of his own compositions, while interpreting an Ellington tune as well as the Harold Arlen classic, “Devil and the Deep Blue Sea.” It wasn’t extraordinary so much as it was compelling to hear just how easily Monk’s style still meshed with the changing times, even though he himself hadn’t really changed at all.

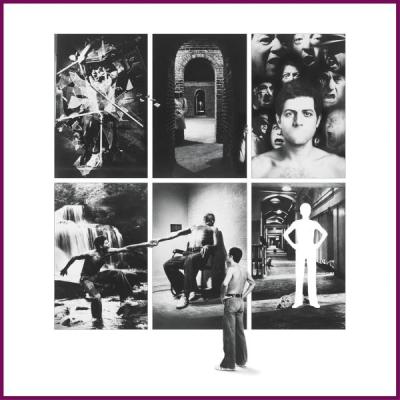

By 1968, though, even a large percentage of rock and roll musicians could no longer keep up with the evolution of pop culture. What was cool in 1967 seemed hopelessly inept by 1968, as music developed an edge brought on by politics, drugs and significant social change. The naiveté of the ‘summer of love’ had been overwhelmed by cultural unrest. In the midst of these tumultuous times, Monk dropped “Underground.” You could judge this record’s relevance by the cover alone (it won a Grammy award for the design), but the content also spoke volumes. The album featured four new Monk compositions, bookended by stunning reinterpretations of two classics from his catalog. Here, at approximately a quarter-century into his career, Monk sounded as relevant and contemporary as he did in 1948, and he did it without changing a single thing. More than just an accomplishment, it was also an unconscious statement of purpose, announcing to the entire world that the music of Thelonious Monk would remain indestructible.

June 1968 – Billboard Did Not Chart

Related Shows