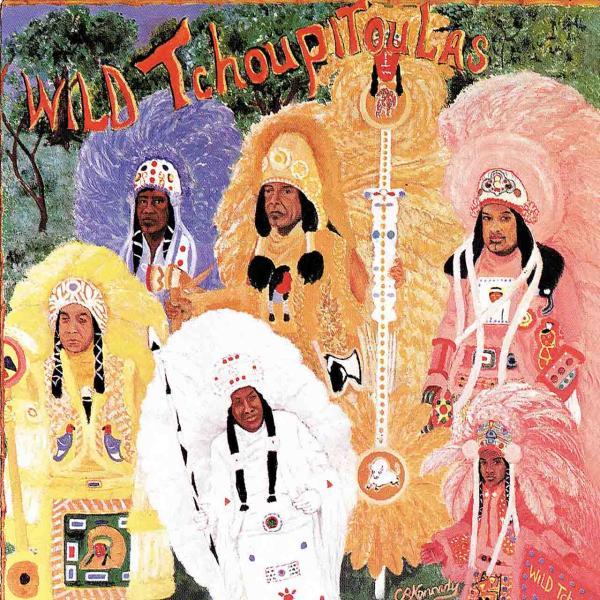

Wild Tchoupitoulas: Wild Tchoupitoulas

Album #215 - June 1976

Episode date - January 7, 2026

I heard “Wild Tchoupitoulas” for the first time circa 1978-1979, and my introduction to the album was pretty strange, which is only fitting for a white boy from suburban New York.

Where I grew up, ‘culture’ meant playing “Danny Boy” on St. Patrick’s Day. Quite honestly, I cannot think of a single cultural tradition beyond Thanksgiving that I shared with my neighbors. On holidays we had parades, but they were astoundingly boring and nobody cared much. Living in a land of strip malls populated by third and fourth generation Europeans, there was literally nothing in my youthful experience that could be called indigenous.

In the late seventies, though, I turned twenty and my natural curiosity abounded. Punk music and the culture that surrounded it started to leak out to the suburbs, and I absorbed it with gusto. Now, punk culture has absolutely nothing in common with Mardi Gras Indians, but in our cloistered world, there were many things that were just inexplicable. For example, a huge part of punk music drew heavily from Jamaican culture and I quickly found myself enamored. The Clash relied heavily on Jamaican dub styles, and punk palaces like The Mud Club would play nothing but Jamaican music, so it seemed natural when I found myself rummaging through record bins for Jamaican reggae and dub. A friend had a nice collection of obscure reggae, and he lent it to me so I could record some of it. In the middle of his pile was “Wild Tchoupitoulas.” Apparently, he couldn’t quite make sense of the album’s derivation either, and presumed that it might somehow be related to reggae, but this had nothing in common with U-Roy, Joe Gibbs, or Junior Murvin. Despite my inability to discern the album’s roots, I fell in love with it, and virtually memorized it, nonsense syllabics and all. For all I knew, it came from Jupiter, but I loved it anyway.

Soon after, I became more and more aware of New Orleans and its incredible cultural mix. I developed a genuine fascination for the place because it was the exact opposite of my own experience thus far. New Orleans was/is almost certainly the most culturally diverse place on earth, and the mash-ups of French, Creole, Spanish, African, American Indian, Caribbean etc., etc., led to complexities that could barely be imagined. Some traditions were so entrenched that even those in the midst of it could not untangle the variety of influences, or even the linguistic root for phrases like “Jockomo fee na nay.” Wild Tchoupitoulas represented a cultural mash-up better than anything else I ever heard, and yet it is pure in its New Orleans heritage. African Americans embrace the Mardi Gras holiday by dressing as American Indians and chanting in a language that can probably be partially traced to Africa, with Creole and Haitian influences. Since it had always been a verbal tradition, pronunciations and spelling changed over centuries. While meanings became scrambled or forgotten, the phraseology did not, and it became a means of identity for African American Mardi Gras Indians. When the Dixie Cups sang “Iko Iko” and it became a hit, most people outside of New Orleans presumed it to be a schoolyard chant, but it was much, much more. The entire parade culture of big chiefs, Indians, spy boys and flag boys is all too much for mainstream America to comprehend, which explains why this record was so misunderstood outside of Louisiana.

“Wild Tchoupitoulas” was an Indian tribe started by ‘Big Chief’ George Landry in the ‘70s, taking their name from an indigenous American Indian tribe. Landry’s tribe included members of The Meters, so the idea of recording Mardi Gras Indian chants must have seemed quite natural at the time. Art Neville played keyboards with the band, and since the record was meant to convey a familial, celebratory spirit, he asked his three brothers to join in on the project, making this a debut album of sorts for The Neville Brothers. Legendary producer and songwriter Allen Toussaint produced the album with Marshall Sehorn, another legendary New Orleans song man, making this one of the most deeply profound New Orleans musical projects imaginable. It comes off as a complete mystery to outsiders, but regardless of where you’re from, it is impossible to shrug off the incantational power of the call and response chants, performed over syncopations that incorporate second line rhythms (yet another strictly New Orleanian cultural phenomenon of celebratory funeral music). Indian tribes would work on stunningly ornate costumes and rehearse their chants all year long, building up to the climactic excitement of Mardi Gras, when they would march and sing their chants along secret parade routes expecting to encounter clashes with other tribes. All of this was completely foreign to me, but I love it now with a passion so deep that feels like a part of me. Most likely, this is completely outside your own realm of experience, but once you let this fascinating amalgamation of cultures get under your skin, it won’t take long before its music is in your blood.

Featured Tracks:

Brother John

Meet de Boys on the Battlefront (melody and rhythm based on Rupert Westmore Grant aka Lord Invader's "Rum and Coca Cola")

Here Dey Come

Hey Pocky A-Way

Indian Red

Big Chief Got a Golden Crown

Hey Mama (Wild Tchoupitoulas)

Hey Hey (Indians Comin')

June 1976 – Billboard Did Not Chart

Related Shows

- 1 of 20

- ››